Daily life: July 2014

"The Genovese Rhapsody"

How do you really make a portrait of a city?

This is a question I have been asking myself for quite a while and since the question itself grows from the mix of two of my deepest passions (photography and travel), its answer sometimes changes depending of the city itself and the connection I establish with it.

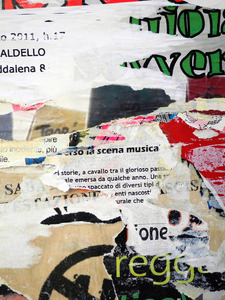

In a visit to Genova (Italy) an answer to that question made itself visible in the multiple corners of the city, thanks to the different layers of advertising posters covering the infinite walls and streets that move around her like a chaotically organized diagram; each poster not only talking about the different aspects of the place and its inhabitants (socially, politically, historically, musically, etc, etc), but acting too as a metaphor of the different cultural layers that compose an urb of such size and history.

Once one of the main entrances to the "Old World", Genova shows us the fingerprints of human history printed in every block, door and streets like many other crossroads points between old and new worlds do. Still today, the whole area boils with the mixed kind of cultural heritage that at the same time gives it its own and unique identity. The identity of a place deeply cosmopolitan but still rooted on its European stage setting of which is part of.

Step by step and block by block I found the compositions that today you see here, and while standing in front of them I could not avoid to create in my mind a mirrored image of what it was in front of me and what was behind, where the overwhelming (but still pleasant) cacophony that covers the air with music, sounds, and voices added to the smells that float in every corner and the constant flashing of images that make you look, stop, and look again making each step a discovery, the discovery of the constant beauty of a place where people from all corners of the world has added their little piece of identity in top of each other, creating a whole and turning Genova into a massive and generous treasure. A feast for the senses.

F. Martín Morante

Constance Bay Triptychs and Multiples 2011 - 2014

Constance Bay in Ontario has always been a place I feel a close connection with. Being here brings me tranquility and peace, and it is an area that I feel mirrors my moods. It has celebrated, grieved, and shared in my emotions in the past. Within my body of landscapes, I seek to communicate these different feelings in hopes that the viewer can relate to such an oasis in their own lives. In a way these pieces are not only spaces of the earth, but self-portraits as well. Keeping rebates in these works add to the artistic intent and mystery of the images.

The Basters

This is the first in a series of portraits that I am doing about the people of Namibia. Namibia is a country shrouded in mystery and wonders to the outside world. Shielded by its remoteness and empty spaces from the world, yet it is alive and bustling with life. The people are divided into at least eleven different ethnic groups in the country. The population can be divided into the following groups, the Owambo, Kavango, Herero, Himba, Damara, Nama, Topnaars,Rehoboth Basters,Coloureds,Caprivians,San,Tswanas and Whites.

A brief history of the first group that I have photographed. The Rehoboth Basters.

In central Namibia lies the Rehoboth Basters people, descendants of European Colonists and Indigenous Khoi-People. During colonial times, they set up their own political system, which guaranteed them the right to self-determination.

The German occupation, however, ended at World War I, and Namibia (formally called South West Africa) became a League of Nations Mandate territory, administered by the Government of the Union of South?Africa.

During the South African occupation, much of the Basters rights were suppressed, and their land alienated. In the late 70’s South Africa passed the ‘Rehoboth Selfgovernment Act’ granting the Basters autonomy, allowing them to grow and develop.

In 1990, Namibia became an independent nation and the Baster self-Government was abolished. Seeing that it was the self-Government itself who owned the Bastercommunal land, with its extinction, all the land was seized and claimed by the newly formed Namibian government.

The Basters are in between cultures, neither belonging to the majority of black Namibian's or the minority white Namibian.

They have truly been in no man's land and are struggling to preserve their identity and their culture. A new generation is now grown up, born in an independent Namibia.